The book “Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls: A History of Slavery in Tennessee” by Bill Carey will correct that belief. By 1860, only one in four white Tennessee families owned slaves. But many people and companies leased slaves (yes, that was a real thing).

The book contains an appendix, listing runaway slaves and their slaveholders’ counties. That includes 74 owners from Shelby County, 23 from Tipton County, 15 from Fayette County and 9 from Haywood County. Those locations hit close to home in the Mid-South.

The book was published April 12 by Clearbrook Press, and signed copies are available in hardcover and paperback at their website. Books are also available at Amazon.com and by special order from any bookstores that don’t already stock it.

The book was published April 12 by Clearbrook Press, and signed copies are available in hardcover and paperback at their website. Books are also available at Amazon.com and by special order from any bookstores that don’t already stock it.

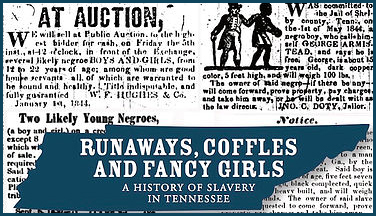

The unfamiliar word “coffle” in the title refers to slaves chained together and being marched along. A “fancy girl” was an attractive slave, usually multiracial and around 12-20 years old, who was sold to be a concubine. Fancy girls were publicly and regularly sold for the sex trade, two blocks west of the Davidson County Courthouse and two blocks east of the Tennessee State Capitol.

Curiosity won out

Carey, a columnist for The Tennessee Magazine for about 12 years, began his journey toward this book when he went to the state library, intending to research and write a column about the first issue of the Tennessee Gazette in 1791. It was the state’s first newspaper and possibly the first published west of the Appalachian Mountains. He noticed there were three or four slavery-related ads in that first issue, and it was only a four-page publication.

“You don’t normally think about slaves being in Knoxville in 1791,” he said. “You just don’t. When we teach about early Tennessee history, we’re talking about John Sevier or Daniel Boone. We teach about the frontier warriors and the Indians. We really don’t talk much about slaves.”

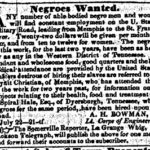

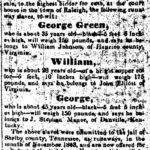

Curiosity got the best of him. He started poring over old papers and was amazed at the level of detail in the ads, some of then 140 or more words long. The ads named a reward and described how the slaves looked and what they wore, included clues about demeanor and personality, listed identifying scars, and guessed at why the slave left and where the runaway was headed (often toward family in the Virginia area).

“I started digging on the slaves and I was determined to find everyone in the Gazette, and I finally finished that.”

Then he turned to other newspapers. By the time he was done, he had compiled runaway slave ads accounting for about 1,500 enslaved people. Archives are incomplete, so he said this research represents only part of the slave activity in Tennessee for the era.

Ultimately, Carey drew upon data from more than 900 runaway slave ads published in Tennessee newspapers from 1792 through 1864, as well as slave trader ads, scholarly books and first-person accounts. In the newspapers, he also started noticing other slave-related ads, including some slave leases, sales and auctions.

Then he delved into Memphis’ history with the slave trade.

The role of Memphis

“You have to learn about Memphis, because Memphis may have had more of the slave trade than any other inland city in America after 1840,” he said. “Nashville doesn’t even compare to Memphis in terms of numbers.”

Carey explained the city’s prominence: After about 1835, Tennessee was actually exporting more slaves than it was importing, usually to Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas. Those were the states under development at that time.

“What city is closest to those four states?” he asked. “Memphis.”

One of the largest firms in the slave trade was Bolton, Dickens & Co., which had eight offices in different cities. In Memphis, they occupied a full square block with a big wall around it to contain the slaves in downtown Memphis. Most of their slaves were sent down river to sell in New Orleans and Natchez. The company collapsed after one of the firm’s chief members was involved in a murder, soiling their reputation.

Nathan Bedford Forrest then took their place in the market, and that’s how he became a millionaire, Carey said.

Slavery in Tennessee

In his research, Carey educated himself on how completely slavery was woven into virtually every level of society: The rich owned them. The less wealthy leased them. And the poorest competed in a job market with wages driven down by slave labor.

Memphis wasn’t alone in being a bedrock for Tennessee’s slave trade: The city of Nashville itself owned 24 slaves. Slaves were given away in state lotteries. There were court-mandated slave sales on the steps of courthouses across the state, including in Raleigh, which was the county seat from 1826 to 1868.

Slavery was vital to the state’s economy and operations at every level. Courts, newspapers, factories, plantation farming and banks — which financed their purchase — accepted slaves as loan collateral and extended lines of credit to professional slave traders.

(Click to enlarge any of the historic slave-related ads below.)

Slaves also worked in factories, mines and homes, and some had special talents in carpentry, shoemaking, masonry, cooking, ironing and other useful skills. Some were even described as engineers. Even the sheriffs that arrested suspected runaways often put them to work to reduce operational costs.

A third or more of the runaway slave ads covered in “Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls” are from Shelby County. Carey noted, however, that the percentage is not necessarily because of the number of slaves or runaways in this area, but because of the spotty availability of archived local newspapers from the period.

By 1860, Tennessee was home to 282,000 black people, but only 2.5 percent were free.

About the author

Carey, who has written five books, is originally from Huntsville, Ala., and has lived in Nashville since 1992. He also is president and founder of Tennessee History for Kids, an organization that organizes resources online and produces inexpensive state history booklets for use in grades 1-5, 8 and 11. Shelby County, Bartlett and Arlington school districts are among the school systems that use the booklets.

Carey, who has written five books, is originally from Huntsville, Ala., and has lived in Nashville since 1992. He also is president and founder of Tennessee History for Kids, an organization that organizes resources online and produces inexpensive state history booklets for use in grades 1-5, 8 and 11. Shelby County, Bartlett and Arlington school districts are among the school systems that use the booklets.

In the preface to “Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls,” Carey writes, “I hope this book results in a greater understanding of slavery in Tennessee. I hope teachers start incorporating more lessons about slavery into their classes, and I’d like to see students doing research about slaves in their home counties. … I’d like us to realize, when we talk about life in Tennessee before the Civil War, that slavery was everywhere.”

He continued, “The last thing I want to do is add to the animosity that already exists in our society. Instead, I hope we can all get a better understanding of our collective story and agree that this part of it must be told.”

For more information, visit tnhistoryforkids.org or clearbrookpress.com. Carey also will appear in the Memphis area later this fall. He will address the West Tennessee Historical Society on Oct. 1 at Memphis University School. He also have many interim appearances planned throughout Nashville.